To transfer a deed from one party to another, you must draft a new deed document. This legal instrument must clearly identify the property, the grantor (the party transferring the property), and the grantee (the new owner). The grantor must then execute the document by signing it before a notary public. Finally, to make the transfer legally binding and enforceable against all parties, the deed must be officially recorded with the appropriate county office.

Laying the Groundwork for a Flawless Deed Transfer

Before any documents are signed, a seamless property transfer begins with meticulous preparation. This foundational stage is not merely about administrative tasks; it's about making strategic decisions that protect all stakeholders and mitigate future risks. For industry professionals, rushing this phase is a direct path to costly legal and financial complications that can damage both your reputation and your bottom line.

Ensuring accuracy from the outset is non-negotiable. A seemingly minor error, such as a misspelled name or an imprecise property description, can create a "cloud on title"—a defect that can completely derail a future sale or refinance, leading to client dissatisfaction and potential liability.

Choosing the Right Type of Deed

One of the first critical decisions is selecting the appropriate type of deed. This choice is paramount as it defines the level of protection—or covenants of title—the grantee receives from the grantor. The optimal choice is entirely dependent on the specific context of the transaction.

Not all deeds are created equal. The instrument you choose dictates the warranties and guarantees being made about the property's ownership history, directly impacting the risk profile of the transaction.

Choosing the Right Deed for Your Transfer

A quick-glance comparison of the most common types of deeds to help you decide which is appropriate for your property transfer scenario.

| Deed Type | Level of Protection for Grantee | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Warranty Deed | Highest Level. Grantor guarantees clear title and will defend against any claims. | Standard, arm's-length real estate sales. |

| Quitclaim Deed | No Protection. Grantor transfers only their interest, whatever that may be, with no guarantees. | Transferring property between family members, clearing title defects, or moving a property into a trust. |

A warranty deed is the gold standard for most residential and commercial sales, offering the buyer maximum assurance. A quitclaim deed, conversely, is best suited for low-risk scenarios where a high degree of trust already exists between the parties.

A common but dangerous mistake is using a quitclaim deed in a standard sale to reduce complexity or cost. While seemingly simpler, the grantee's lack of protection can lead to disastrous consequences if a prior title issue emerges.

Gathering the Essential Information

Once the deed type is determined, the next step is to compile the precise information required for the document. Absolute accuracy is critical. The property’s official legal description is required—a street address is insufficient. This description can be found on the current deed or within the county's public records.

You also need the exact, full legal names for both the grantor and grantee. Nicknames or abbreviations are unacceptable; names must match official government-issued identification. For professionals like title abstractors and their workflows, meticulous verification of these details is a cornerstone of their due diligence process.

Understanding the Financial Implications

Finally, do not overlook the financial components. Transferring a deed involves costs that vary significantly by jurisdiction. Taxes are a major factor. Globally, the average property transfer tax is approximately 3.3%, but it can be substantially higher in certain jurisdictions. In Belgium, for example, it can reach as high as 11.3%!

These fees can add a significant cost to the transaction. It is essential to research your local requirements thoroughly to budget correctly and advise clients accurately. Completing this financial due diligence upfront prevents unwelcome surprises at closing.

Drafting and Executing the Deed Document Correctly

Once all essential information is gathered, you can proceed to draft the deed. This phase demands extreme precision, as the deed is a legal instrument where a minor error can have major consequences.

A typo, an incorrect legal phrase, or a missing signature can invalidate the entire document. These simple errors often create costly title defects that can encumber a property for years. A deed is the legal blueprint for an ownership transfer; every detail, down to the margin size on the paper, must comply with local statutes, or the county recorder's office will reject it.

Deconstructing the Key Clauses in a Deed

A deed is composed of several critical clauses, each serving a specific legal function. Understanding these components is key to appreciating why every word matters and why precision is non-negotiable for a successful transfer.

The following components are found in a standard deed:

- Granting Clause: This is the core of the document, containing the explicit language through which the grantor conveys their ownership interest to the grantee. It employs specific legal verbiage, such as "grant, bargain, and sell" or "convey and warrant."

- Habendum Clause: Often identifiable by its opening phrase, "To have and to hold," this clause defines the type of ownership estate being transferred. For example, it clarifies whether the ownership is absolute (fee simple) or subject to conditions or limitations.

- Consideration Statement: This clause states the value exchanged for the property. While often a monetary amount, a nominal sum like "$10 and other good and valuable consideration" is frequently used in deeds for gifts or inter-family transfers.

- Legal Description: As previously noted, this is the official, detailed description of the property's boundaries, not the common street address. An error in the legal description is one of the most common and severe mistakes in deed preparation.

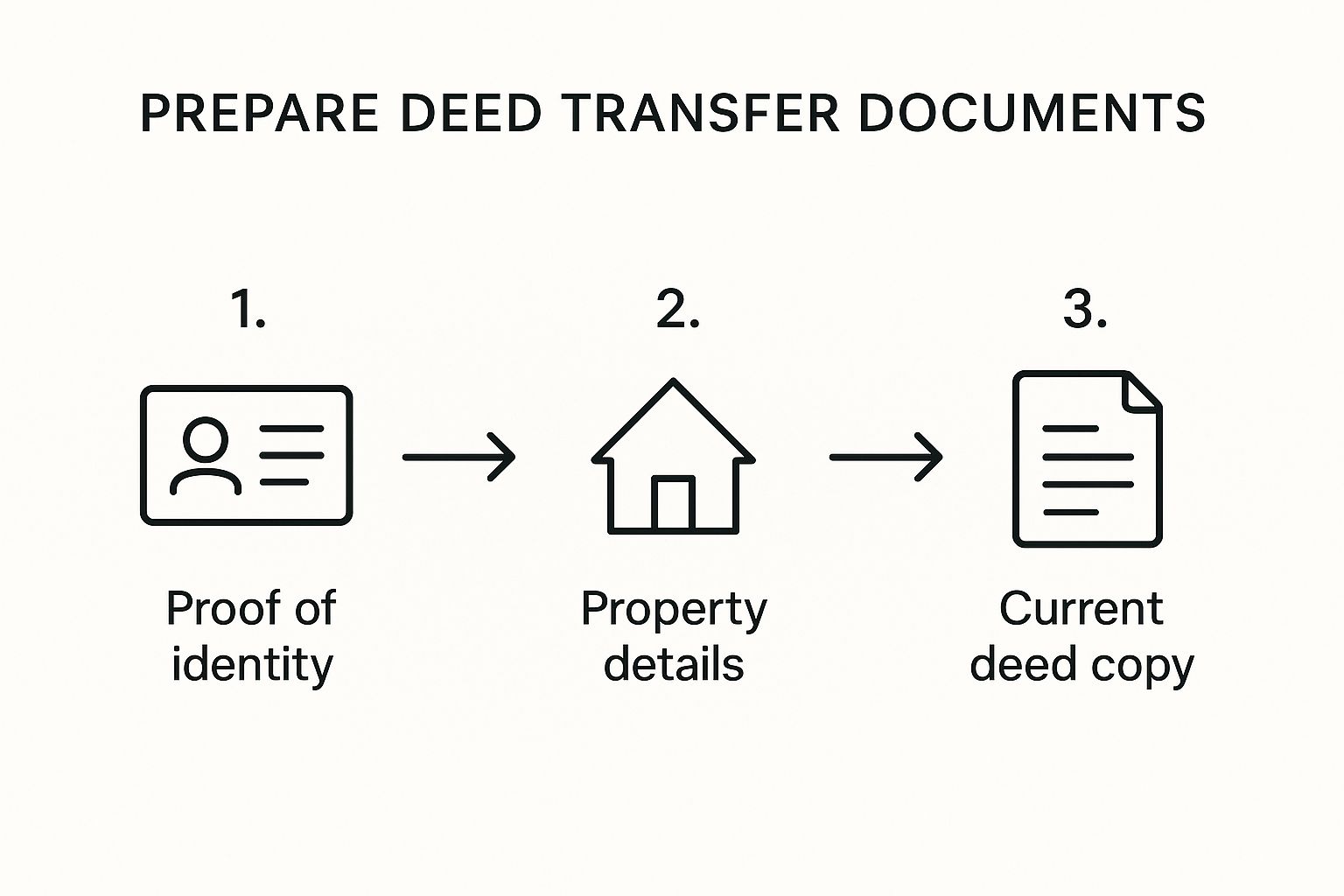

Before drafting these clauses, three foundational pieces of information must be confirmed, as illustrated below.

This visual underscores a critical point: before any legal language is drafted, the core elements—the parties involved, the precise property details, and the existing ownership documents—must be flawlessly verified.

The Critical Role of Notarization

Once the deed is drafted, it must be properly executed. This requires the grantor to sign the document in the presence of a notary public. Notarization is not a mere formality; it is an absolute requirement for a deed to be legally valid and recordable in public records.

A notary public serves as an impartial witness, verifying the signer's identity and confirming they are acting of their own free will.

A deed lacking valid notarization is effectively worthless for public recording. A transfer was once delayed for months because the notary's commission had expired the day before the signing. The entire document had to be re-drafted and re-executed, causing significant client frustration and additional costs.

This illustrates how a minor detail can derail the entire process. The notary must affix their official seal or stamp and clearly state their commission expiration date.

Avoiding Simple but Costly Formatting Errors

Beyond the legal language, the physical format of the deed must adhere to state and local regulations. These requirements can be surprisingly specific and are a common reason for rejection by county clerks.

Common formatting rules often include:

- Paper Size and Quality: Many jurisdictions mandate standard 8.5 x 11-inch paper of a specific weight.

- Margin Requirements: Strict margin rules are enforced to leave space for official recording stamps, such as a 3-inch margin at the top of the first page.

- Font and Text Size: The text must be legible, with many offices requiring a minimum font size, like 10-point black ink.

For title professionals managing files across multiple counties, tracking these local nuances is a significant operational challenge. A single formatting error results in rejection, halting the workflow and delaying closing. This is where a robust, automated system becomes indispensable. A platform like TitleTrackr can automatically flag documents that fail to meet specific county requirements, catching these time-consuming errors before they leave your office and ensuring a much smoother, more efficient transfer process.

Making It Official: Recording Your New Deed

A perfectly drafted and notarized deed is merely a private agreement until it is officially recorded with the government. Recording the new deed is the final and most crucial step, as it makes the property transfer legally binding and creates a permanent, public record of ownership.

This public notice solidifies the new owner's rights and serves as the ultimate defense against future claims or title disputes. Failing to record a deed leaves the new owner’s claim to the property legally vulnerable.

Finding the Right Office to Record Your Deed

First, you must identify the correct local government agency for filing. This is not a generic courthouse; it is a specific office whose name can vary by location.

Depending on the county or state, you may be looking for:

- The County Recorder

- The Register of Deeds

- The County Clerk's Office

- The Land Registry Office

A quick online search for "[Your County Name] property records office" is typically the most efficient way to confirm the correct agency. Filing in the wrong jurisdiction will result in rejection, leading to frustrating and unnecessary delays.

Recording a deed is not just a formality; it's the action that legally perfects the new owner's title. An unrecorded deed, while potentially valid between the grantor and grantee, offers zero protection against claims from third parties, such as creditors or subsequent purchasers.

Getting a Handle on the Costs

Filing a deed incurs fees that must be paid at the time of submission. These costs can vary significantly depending on the property's location and value.

The primary expenses include:

- Recording Fees: This is the administrative fee charged by the county for entering the document into the public record. It is often calculated per page, meaning more complex deeds may have higher recording costs.

- Transfer Taxes: This is typically the most substantial expense. Many states, counties, and municipalities levy a tax on the transfer of real estate, usually calculated as a percentage of the property's sale price or assessed value.

For example, a 1% transfer tax on a $400,000 property sale results in a $4,000 tax liability that must be paid before the deed can be recorded. Always verify local transfer tax rates in advance to accurately calculate closing costs and advise your clients.

The Submission and Confirmation Process

Once you have identified the correct office and calculated the fees, the final step is submitting the deed. You must present the original, signed, and notarized document; photocopies are not accepted. The clerk will review the document to ensure it complies with all local formatting and content requirements.

After accepting the document and payment, the clerk's office will:

- Stamp the deed with the official date and time of recording.

- Assign it a unique identification number, often a book and page number.

- Scan the document to create a digital copy for the public record.

The original document, now bearing official recording information, is typically mailed back to the new owner or their representative within a few weeks. This stamped original is the ultimate proof of ownership. The sheer volume of these transactions underscores their economic importance. In a single recent month, Spain registered 185,546 property transfers, with urban properties accounting for 87.4% of that total. You can explore more details on these property transfer trends to appreciate the scale of this activity.

For professionals handling a high volume of transfers, the traditional in-person recording process can be a significant bottleneck. This is where modern tools can revolutionize your workflow. Platforms like TitleTrackr integrate e-recording capabilities, allowing for instant, secure digital submission to participating counties. This not only accelerates the process but also provides immediate confirmation and a secure digital archive, making the final step of a deed transfer more efficient than ever.

Navigating Tax and Financial Considerations

A deed transfer is not just a legal procedure; it is a significant financial event with complex tax implications. Overlooking these financial aspects can lead to substantial and unexpected liabilities for your clients.

Beyond standard recording fees, several taxes can be triggered by a property transfer. Failing to account for them can turn a simple transaction into an expensive and complicated ordeal. Let's break down the key financial hurdles that professionals must navigate.

Unpacking the Different Types of Taxes

When a property changes hands, government entities expect their share. The specific taxes depend on the nature of the transaction and its location, but they generally fall into several categories.

Key tax considerations include:

- Transfer Taxes: These are state and local taxes levied when property ownership is transferred. They are typically calculated as a percentage of the sale price or fair market value. The responsible party—buyer or seller—is often determined by local custom and negotiation.

- Gift Taxes: Transferring a property for less than its fair market value may trigger federal gift tax. The IRS allows for an annual exclusion amount per recipient, but any value transferred above this threshold could be taxable and require filing a gift tax return.

- Capital Gains Taxes: The grantor (seller) may be liable for capital gains tax if the property is sold for more than its cost basis. The profit is considered a capital gain and is subject to federal and potentially state taxes.

A common misconception among clients is that quitclaiming a property to a family member is a simple, tax-free event. This is a significant error. While it may avoid transfer taxes in some jurisdictions, it can create immediate gift tax issues for the grantor and a larger capital gains tax liability for the grantee in the future. Professional tax advice is essential.

The Ripple Effect on Property Taxes

A frequent and often overlooked consequence of a deed transfer is its impact on property taxes. A change in ownership typically triggers a reassessment of the property's value by the local tax assessor.

This reassessment can result in the property's taxable value being adjusted to its current market price. If the property has not been reassessed for a significant period, the new owner could face a substantial and immediate increase in their annual tax obligations. This is a critical factor to include in financial planning, especially in appreciating real estate markets.

Special Considerations for Commercial Properties

For commercial real estate, the financial stakes are even higher. Transfer taxes, in particular, can have a profound impact on transaction viability. Data indicates that for every 1% increase in transfer tax rates, property values tend to decrease by 1%, and transaction volume falls by approximately 8%.

Many jurisdictions impose transfer taxes on commercial properties in the 3% to 5% range. This can significantly erode a property's value and deter market activity. You can read the full research about these economic effects to understand the full impact. For any developer or investor, these taxes are a major line item that must be factored into financial models from the outset.

Managing these complex financial details across multiple properties and jurisdictions is a monumental task. The risk of miscalculation or a missed deadline is extremely high. A centralized system is no longer a luxury but a necessity for risk management. A platform like TitleTrackr is engineered to help professionals manage these document-heavy workflows, ensuring every financial and legal detail is tracked with precision. By automating data extraction and reporting, you can navigate these challenges with confidence, knowing nothing is overlooked. Request a demo with TitleTrackr to see how you can gain control over your entire transfer process.

Sidestepping Common and Costly Transfer Blunders

In the realm of deed transfers, a minor oversight can escalate into a major title issue, leading to legal disputes and significant financial losses. Understanding how to transfer a deed correctly involves knowing which common pitfalls to avoid.

This section serves as a guide to the most frequent—and damaging—errors encountered in the industry, highlighting their real-world consequences so you can proactively prevent them.

The Danger of a Flawed Legal Description

One of the most prevalent errors is an incorrect legal property description. Many mistakenly believe a street address is sufficient, but legally, it is not. A deed requires the precise legal description filed in county records, which may include metes and bounds, lot numbers, or subdivision names.

Consider this scenario: a parcel is transferred, but the description incorrectly includes a ten-foot strip of a neighboring property. Years later, the new owner attempts to build a fence, and the error is discovered. This leads directly to a boundary dispute, a quiet title action, and the potential need to purchase land they believed they already owned.

Name Misspellings and Their Lasting Impact

While it may seem trivial, a misspelling of the grantor's or grantee's name can create a significant "cloud on title." When a name on a deed does not perfectly match public records or legal identification, it disrupts the chain of title.

Real-world example: Johnathan A. Smith sells his property, but the deed is recorded under "Jon Smith." Years later, when the new owner tries to sell, a title search flags the discrepancy. Lenders and buyers will halt the transaction until this cloud is cleared, a process that may require a corrective deed or even a court order, causing months of delays and thousands in legal fees.

The legal system demands absolute precision. A deed is a permanent record, and any ambiguity can undermine its validity. An incorrect middle initial can bring a future transaction to a grinding halt until the issue is formally resolved.

Choosing the Wrong Tool for the Job

As discussed, different deeds offer varying levels of protection. Using a quitclaim deed in a standard arm's-length sale is a critical error for the buyer, as it provides no guarantee that the seller holds the title free and clear of encumbrances.

This shortcut is sometimes used in an attempt to save costs but exposes the buyer to immense risk. The grantee receives only the interest the seller possessed—which could be nothing. This is one of many areas where professional guidance can prevent a catastrophe. Explore more industry insights on our real estate and title industry blog.

Failing to Execute and Record the Right Way

A perfectly drafted deed is worthless if it is not properly signed, notarized, and recorded. A forgotten signature, an expired notary seal, or filing with the incorrect county recorder’s office are all critical failures that can invalidate the entire transfer.

An unrecorded deed offers the new owner no public protection. The original owner could legally sell the property to another party, or their creditors could place a lien against it, leaving the new "owner" with a legally unenforceable claim.

How to Prevent Errors Before They Happen

These mistakes underscore the critical need for a system that catches errors before they become permanent, costly problems. Manual review processes are susceptible to human error, particularly when managing a high volume of complex documents. This is where dedicated title management technology provides immense value.

A platform like TitleTrackr is designed to serve as your operational safety net. It can automatically flag inconsistencies in legal descriptions, name mismatches, and other common errors during the drafting phase. By ensuring accuracy from the start, you avoid the expensive and time-consuming process of curing title defects later. Request a demo with TitleTrackr to see how you can build a workflow that prevents these common mistakes and protects every transaction.

Your Questions on Deed Transfers Answered

Even with a detailed guide, specific questions will arise during a deed transfer. Every transaction has unique complexities, and seeking clarification before execution is always the prudent course of action. Here are some of the most common questions from industry professionals.

Can I Transfer a Deed Myself or Do I Need a Lawyer?

While it is legally permissible for an individual to handle a deed transfer on their own, it is highly inadvisable for professionals managing client assets. The legal requirements are rigid, and a single mistake can create significant liability and title issues that may not surface for years.

For virtually any transaction, particularly property sales or transfers involving mortgages, engaging a real estate attorney or a reputable title company is a sound investment. Their expertise ensures the transfer is legally sound and that your client's interests are protected.

What Is the Difference Between a Deed and a Title?

This distinction is fundamental for professionals.

Title is not a physical document but a legal concept representing a bundle of ownership rights to a property.

The deed, conversely, is the legal instrument—the physical paper—that is executed to transfer that title from one party to another. Recording the deed serves as public notice that the title has officially changed hands.

Understanding this is critical. The deed is the physical tool used to legally move the abstract concept of title from the grantor to the grantee. Both must be handled with absolute precision.

How Long Does the Deed Transfer Process Take?

The timeline can vary significantly. Drafting and executing the deed can often be completed in a single day, provided all parties are prepared.

The primary variable is the government recording process. Jurisdictions with modern e-recording systems may have the transfer officially recorded within a day or two. However, counties relying on mail-in or in-person filings may take anywhere from a few days to several weeks. It is always best practice to check with the local recorder's office for their current processing times to set realistic client expectations.

What Happens If a Deed Is Never Recorded?

An unrecorded deed creates a critical vulnerability for the new owner. While the document may be valid between the signatory parties, it has no legal effect on third parties because the public record remains unchanged.

This leaves the new owner exposed. For instance, the original owner could fraudulently sell the property again, or a creditor could place a lien on it—and the public record would support their claim.

Recording the deed is the ultimate act of protection. It provides official public notice that establishes the new owner's rights against all other claims. For more answers to specific scenarios, you can find a wealth of information in our deed transfer FAQ section.

Managing the intricate details of deed transfers across multiple jurisdictions is a complex challenge. Ensuring every document is precise, properly recorded, and free of errors is non-negotiable for protecting your clients and your business. TitleTrackr leverages AI to automate these document-heavy workflows, identifying potential issues before they become expensive problems and bringing clarity to your entire process. Request a demo with TitleTrackr to see how you can gain control and confidence in every transaction.